We All Deserve Equal Protection

/. . . nor [shall any State] deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

U.S. Const., amend. XIV, § 1.

Humans, like their primate ancestors, possess an innate sense of fairness. This surely mattered in Mesoamerican history, and as our greatest President once said, modern America was “dedicated” in 1776 [1920] “to the proposition that all [people] are created equal.”

So how come the federal government subsidizes homeowners’ mortgage interest (and roads), but not most renters’ rent payments (to say little of public transit)? Why can local governments dictate that people must own 5,000 square feet of land in order to own any land at all?

The honest answer is that America (today) enables socialism for the rich by rigging the markets against everyone else. This violates our national creed.

THE EQUAL PROTECTION OF THE LAWS

When Abraham Lincoln delivered the Gettysburg Address in 1863, the Fourteenth Amendment didn’t yet exist to guarantee “the equal protection of the laws.” Lincoln was deeply unpopular throughout his first term, having won the 1860 election with just 39 percent of the vote. Lincoln also never went to law school, and had the greatest legal career of the nineteenth century.

Lincoln will be proven right in the end. The Fourteenth Amendment made “the equal protection of the laws,” a popular theme from “conventions of free Blacks prior to the Civil War,” a basic tenet of American jurisprudence. Barnett & Bernick, The Original Meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment 324–26 (2021). But the Supreme Court took decades to get this right just about public schools. The Court still hasn’t gotten it right about housing.

After the terrible triplet of The Slaughter-House Cases, 83 U.S. (16 Wall.) 36 (1873), United States v. Cruikshank, 92 U.S. 542 (1876), and The Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3 (1883), the Supreme Court needed to redeem itself. Redemption began with Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356, 361 (1886), where SCOTUS rebuked the San Francisco board of supervisors’ exercise of “a naked and arbitrary power to give or withhold consent.” (Bureaucracies, once founded, last forever.) In 1880, San Francisco’s nouveau riche—not knowing earthquakes make brick buildings dangerous there—made “wooden buildings” illegal without the board of supervisors’ “consent.” Then in 1885, the board revoked its consent for Chinese immigrant laundry owners (while letting the whites all carry on). When the Chinese went on working anyway, the city threw them in jail. See id. at 374. (The Supreme Court of California thought this was fine. Id. at 360.) SCOTUS did the right thing and ordered the Chinese laundry owners released from jail. Id. at 374.

-

San Francisco’s behavior toward its Chinese population remained typical across California into the twentieth century, and a sore subject into the twenty-first. Compare Marino, in Monterey County Weekly (May 12, 2022) (active voice), with City of Pacific Grove, Historic Context Statement 43 (Oct. 31, 2011) (passive voice).

So began a long tradition of California showcasing America’s wackiest hypocrisies. The Supreme Court decided Yick Wo the same day as Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific Railroad Co., 118 U.S. 394, 396 (1886), which found the Fourteenth Amendment protects corporations equally, too. This is a good rule that American litigiousness and modern media have since twisted out of shape. (For nuance, read Horwitz, Santa Clara Revisited: The Development of Corporate Law Theory, 88 W. Va. L. Rev. 173 (1986).)

SEPARATE RESIDENTIAL DISTRICTS ARE INHERENTLY UNEQUAL, TOO

In American law, the phrase “separate but equal” refers to Justice Harlan’s dissent from Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537, 552 (1896). No dissent has ever become more well-respected.

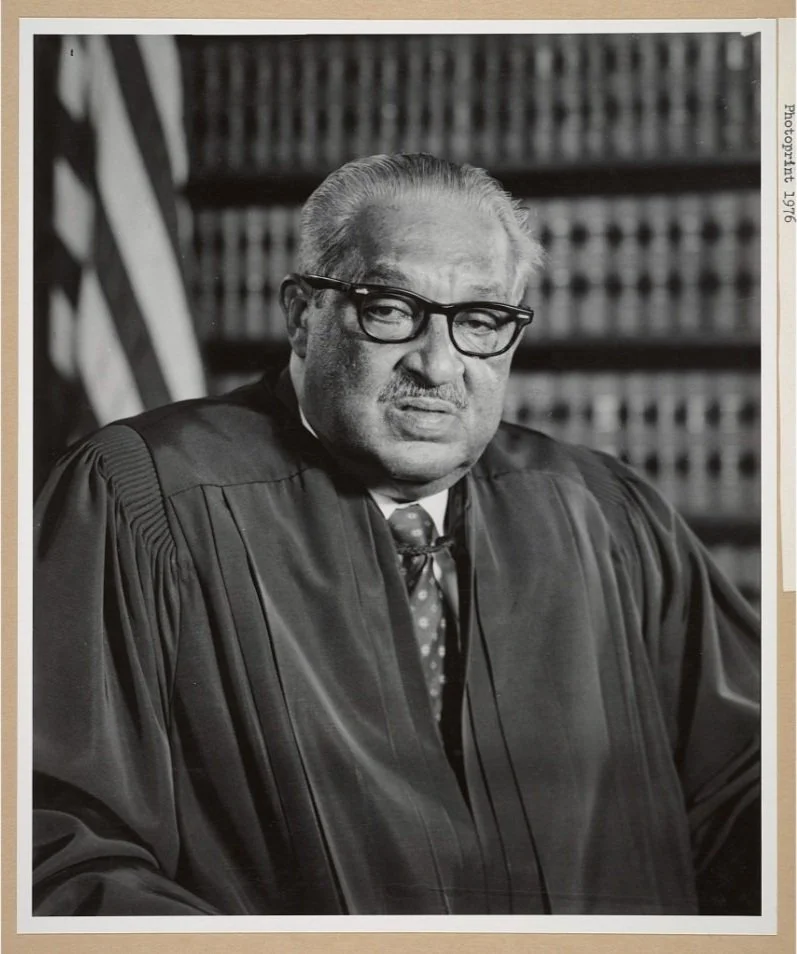

The Supreme Court overruled Plessy in Brown v. Bd. of Educ., 347 U.S. 483, 495 (1954) (9-0 decision) (“Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.”). Thurgood Marshall of the Legal Defense Fund litigated Brown, and that’s why President Johnson appointed Marshall to the Court in 1967. Brown was rightly decided, and Justice Marshall had the greatest legal career of the twentieth century.

Separate residential districts are inherently unequal, too. But the Supreme Court applies a “rational basis” version of the Equal Protection Clause to zoning, so long as governments manage not to write the racism into the literal text of the zoning ordinance. Cf. Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U.S. 60 (1917) (can’t say the quiet part out loud). For one thing, the Court, in a Justice Douglas opinion, ruled that lower federal courts should make up legislative history if it helps to defend legislative line-drawing. Williamson v. Lee Optical of Okla., Inc., 348 U.S. 483, 487–88 (1955); see Barnett, Judicial Engagement Through the Lens of Lee Optical, 19 Geo. Mason L. Rev. 845 (2012).

* * *

We’ll enter the pivotal 1970s in our next post.