"We're from California."

/California infuriates me sometimes. I’ve returned to Berkeley after two months in Tucson and El Paso, and I have to say: it was nice being able to talk about housing without talking about housing elements. “RHNA” isn’t a word in Arizona. But the interior Southwest has a housing crisis too, and it’s connected to California’s.

I know this from experience.

For seven years, California was an expensive place I could sort of afford on vacation. I had a job I liked in Arizona, where I could rent a minimally maintained two-bedroom for $815 (2015) and, after a couple raises, a nicely renovated two-bedroom for $1250 (2017). Rents were stable enough until the pandemic.

“We’re from California.” Confined to my uptown Phoenix apartment in the summer of 2020, it was impossible not to overhear the real-estate agents and the moving trucks. My then-girlfriend’s S.F.-based coworkers all relocated to Phoenix. My landlord suddenly wanted, and surely found an ex-Californian to pay, $1450. Saving was trendy then, so back down the housing ladder I went to a crappy corporate studio apartment for $1280 (2021). The building was full of ex-Californians. When it was time to renew, Weidner Apartment Homes tried gouging me for $1640 (2022). But the building, whose elevator had been broken for two months, hadn’t gotten 28% better. And there wasn’t a smaller unit for me to downsize to, so I told Weidner I would get lost. I’ll never forget commiserating with another soon-to-be-ex-Phoenician, similarly determined not to let Weidner rip him off, carrying his own furniture down the stairwell the day I moved out.

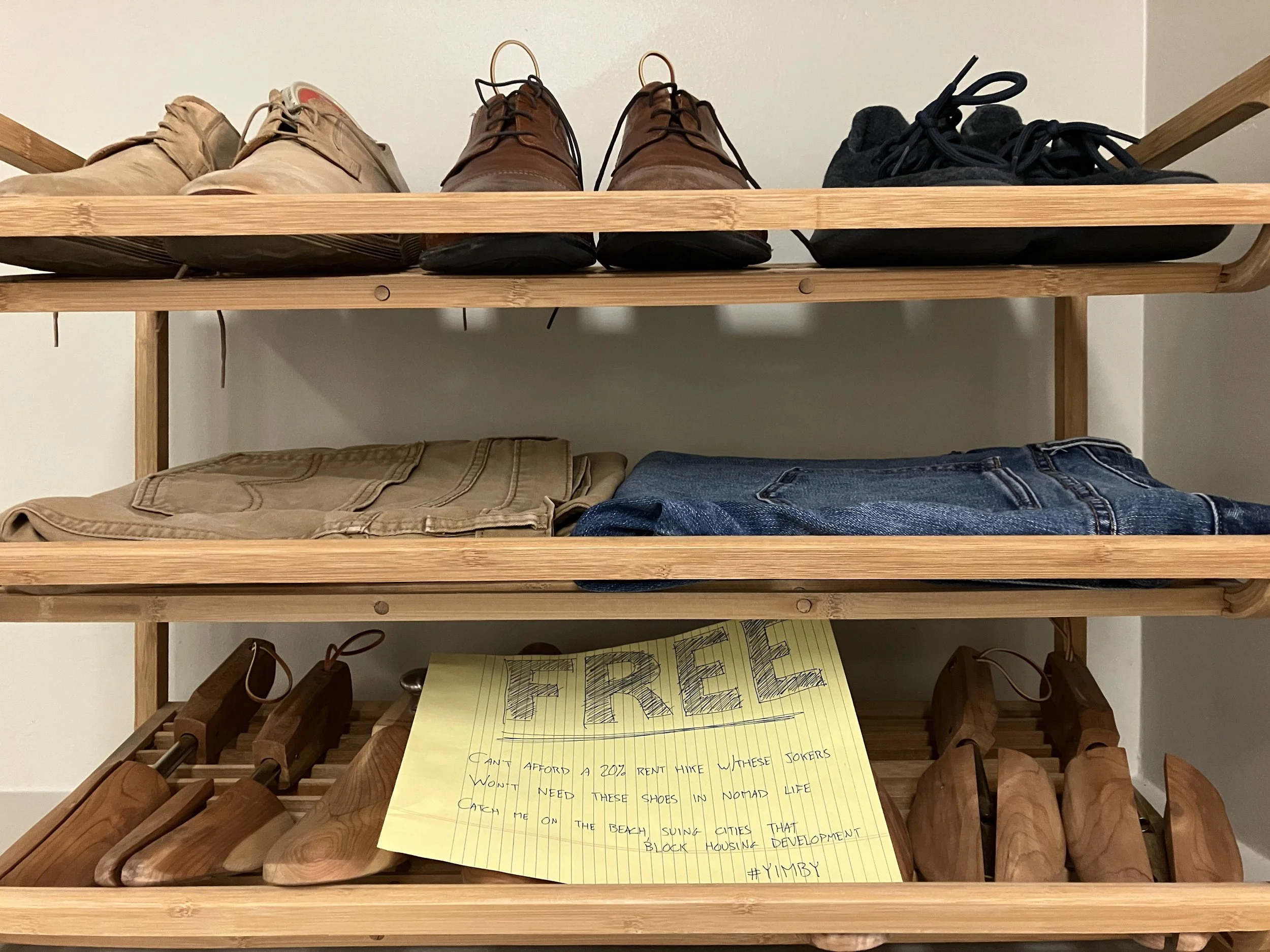

Can’t have a shoe rack when your home is a Miata

Something weird has happened in the housing market: short-term housing has become cheaper than long-term housing. All over the country, there are spare bedrooms and backyard sheds with monthly discounts on Airbnb. That’s how I’ve been living since May. I’ve saved thousands, even up and down coastal California, compared to what my former studio apartment in sonoran Arizona would have cost me. The ADU I just rented in El Paso was only $925.

Yes, the freedom is nice. I do not miss having a landlord, and you’re kidding if you think I’m taking a 30-year mortgage at these prices. But there is a day every month when I can’t leave my car. And there are entire months, depending on the layout and my hosts and their pets, when I can’t cook or use the bathroom at night. There’s a lot to be said for having a home.

California started this crisis, and it needs to fix it. That’s what motivated me to come work here. After a year in and out of the state, though, I can’t help but feel like Californians forget there are 49 other states affected by its housing crisis too. Being less equal than anywhere west of Louisiana, the state codifies an eleven-syllable term for equality and calls itself a leader. Housing elements are a lot of labor and bickering and bureaucracy for a half-million pages that aren’t real-world housing, and I can’t say what good they are unless they just legalize housing. (Thank you, Alameda.)

I’m done posting every week for a while. California law is too much. There will still be a housing shortage after Bay Area housing elements come due next week, I’m busy tracking where the builder's remedy might apply, and I’ve got lawsuits to prepare. You’ll hear about them next time I post.